Has this happened to you? You open an email from one of your students that reads, “I can’t access the required reading file in week 3 of the Canvas course?” Concerned, you open your Canvas course. You check your week 3 module; it’s published and so is your “Required Readings” page. Strange. You open the course page and click on the link to the reading file; it downloads. Even stranger. Your student still insists that they cannot access the file. What is going on???

Instructors working in Canvas can occasionally encounter scenarios like the above where a link, image, or file in their Course works for them but does not work for their students. These errors can be very tricky to diagnose and are often caused by something sneaky going on “under the hood” in Canvas. Thankfully, Canvas has a tool that instructors can use to hunt out bad links in their course. This post introduces Canvas’s course link validator tool and explains how it can be used to proactively detect broken links in your courses. It will also provide a few tips for fixing these issues once they’ve been detected and best practices for avoiding these issues altogether.

Detecting Broken Links

Your secret weapon in this fight against broken links is the course link validator. The course link validator, which can be accessed from the Settings page of your course, scans all content in a course for links that may not work for any of several reasons. It will detect and report links to unpublished content, links to content in another course, and links to external websites that just don’t work. It’s a great idea to run the link validator right before you are ready to publish your course and run it again each time you make a large change or addition.

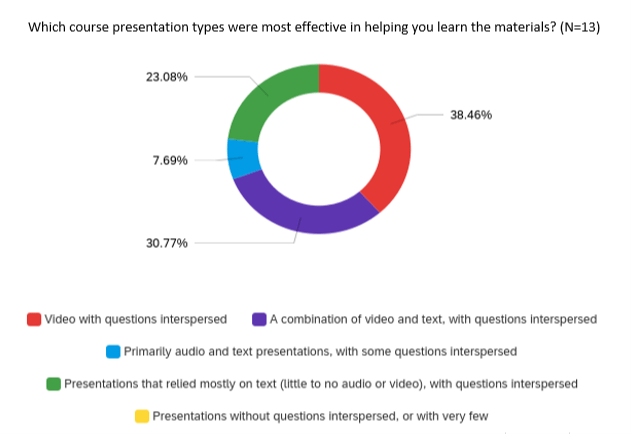

After running the link validator, Canvas will display a list of each piece of content in your course that contains at least one link that may need your attention. These problematic links are further sorted beneath a description of the cause of the error. In the example screenshot of link validator results below, the validator found five broken links in this course:

- One embedded image in a quiz question that will not work for students because the embedded image is stored in another course.

- Three links within a single page that students cannot access because each link points to an object in another course. This page has a link to a page in another course, an embedded image stored in another course, and a link to a file stored in another course.

- A link in a different page that points to an assignment in this course that has not yet been published.

These results illustrate two of the most common causes for confounding broken links in a course:

- Links pointing to unpublished files or other unpublished course content

- Links pointing to content that is in a different Canvas course

Both of these issues create links that appear to work fine for the instructor but do not work for students. Without a tool like the course link validator, it would be very difficult to detect these issues!

Defeating Broken Links

Whenever the link validator detects a broken link in your course, it’s time to spring into action and heal those links. Mending links that are broken because they point to unpublished content is straightforward: find that content in your course and publish it! Fixing links that point to content in other courses is trickier.

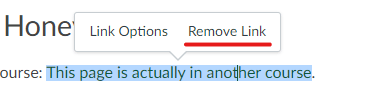

First, you need to remove the bad link. To do this, find the course content that contains the bad link and edit it. Then remove the bad link or embedded image:

- For broken links, find the course content that contains the bad link, click edit, click the link in the editor, then click Remove Link.

- For broken embedded images, put your text edit cursor after the image and backspace to remove it.

Once the bad link is removed, use the Canvas editor’s tools to create a new link that points to the course file or course page, or embed the image from your course images. If that file, page, or image you are linking to doesn’t yet exist within the course, you’ll have to upload it from your computer or import it from the other course. Recreating the link in this fashion will point it at content that is contained within the same course, ensuring your students get to where they need to go!

Why Broken Links Happen

These sneakily broken links are typically the result of a teacher trying to share something with their students that their students are not allowed to access. Naturally, teachers are afforded much wider access to a course than students. The most confusing broken links commonly point to either unpublished content or content in another course. Students can’t see unpublished content or content in the teacher’s other courses, but the teacher can!

One item type in a Canvas course that can unexpectedly cause access problems with its published status is course files. Unlike most other content in a Canvas course, you typically don’t have to manually publish course files; most files you upload to a course will be published upon upload. However, files or even entire file folders can be unpublished in your course Files page. When that happens, students will receive access denied messages after attempting to click a link to that file. To resolve this issue, the course instructor must publish the file or folder in the course’s Files page.

Links to content in another Canvas course can sneak in whenever course content is manually copied from one Canvas course and then pasted into another course. The result of copying and pasting between courses creates links to files, pages, and images that point to an outside course. When students try to follow these links, Canvas sees that they are not enrolled in that course and sends an “access denied” message. To prevent this type of broken link, never copy and paste links or images from one Canvas course into another. Instead, use Canvas’s copy and import tools whenever you need to duplicate content from one course to another.

Try it Out!

Whether or not you have been bitten by broken links in the past, we encourage you to run the link validator in your Canvas courses. If the validator finds any issues, take a look at those pages in your course and either remake those links or publish any unpublished link targets. You can check to see if your fixes were successful by rerunning the validator and using student view to try the links as the test student. If you’re ever unsure of how to fix an issue reported by the link validator, please don’t hesitate to contact Canvas 24/7 support via the “Help” button in Canvas, email UWGB’s Canvas support team at dle@uwgb.edu, or request a CATL Consultation for one-on-one training on finding and fixing broken links!

It is perhaps because of the focus on providing remote students all of the same information and activities that we can sometimes forget to include “us.” Online education can often devolve into a series of tasks that one checks off. We meander into holding virtual correspondence courses, silently reviewing student homework, assessments, and discussion posts and assigning scores.

It is perhaps because of the focus on providing remote students all of the same information and activities that we can sometimes forget to include “us.” Online education can often devolve into a series of tasks that one checks off. We meander into holding virtual correspondence courses, silently reviewing student homework, assessments, and discussion posts and assigning scores.