Multiple-choice quizzes are one of the most common forms of assessment in higher education, as they can be used in courses of nearly every discipline and level. Multiple-choice questions are also one of the quickest and easiest forms of assessment to grade, especially when administered through Canvas or another platform that supports auto-grading. Still, like any assessment method, there are some contexts that are well-suited for multiple-choice questions and others that are not. In this toolbox article, we will provide some evidence-based guidance on when to leverage multiple-choice assessments and how to do so effectively.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Multiple-Choice Assessments

Multiple-choice assessments are a useful tool, but every tool has its limitations. As you weigh the strengths and weaknesses of this format, remember to consider your course’s learning outcomes in relation to your assessments. Then, once you’ve considered how your assessments align with your outcomes, determine if those outcomes are well-suited to a multiple-choice assessment.

Objectivity

Multiple-choice assessments are a form of objective assessment. For a typical multiple-choice item, there is no partial credit — each answer option is either fully correct or fully incorrect, which is what makes auto-grading possible. This objectivity is useful for assessing outcomes in which students need to complete a task with a concrete solution, such as defining discipline-specific terminology, solving a mathematical equation, or recalling the details of a historical event.

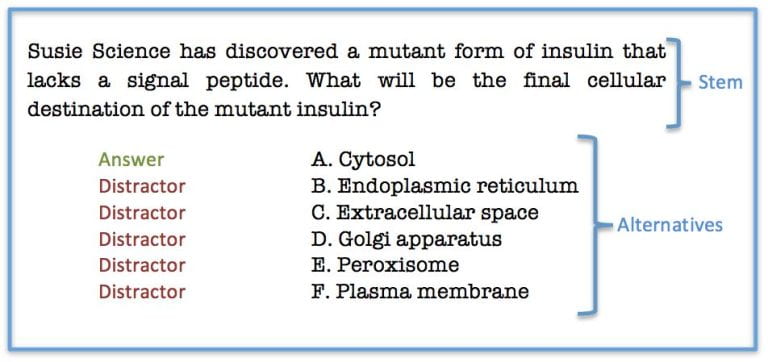

The tradeoff of this objectivity is that “good” multiple-choice questions are often difficult to write. Since multiple-choice questions presume that there is only one correct answer, instructors must be careful to craft distractors (incorrect answer options) that cannot be argued as “correct.” Likewise, the question stem should be phrased so that there is a definitively correct solution. For example, if a question is based on an opinion, theory, or framework, then the stem should explicitly reference this idea to reduce subjectivity.

Example of Subjective vs. Objective Question Stem

Instead of this...

____ needs are the most fundamental for an individual's overall wellbeing.

- A) Cognitive

- B) Self Esteem

- C) Self-Actualization

- D) Physiological

(Answer: D)

Try this...

According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, ____ needs are the most fundamental for an individual's overall wellbeing.

- A) Cognitive

- B) Self Esteem

- C) Self-Actualization

- D) Physiological

(Answer: D)

This version of the question stem clarifies that this question is based on a framework, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, which increases the question's objectivity, and therefore its reliability and validity for assessment.

Another caution regarding the objectivity of multiple-choice questions is that answers to these test items can often be found through outside resources — students’ notes, the textbook, a friend, Google, generative AI, etc. — which has important implications for online testing. Experts in online education advise against trying to police or surveil students, and instead encourage instructors to design their online assessments to be open-book (Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching, p. 106).

Open-book multiple-choice questions can still be useful learning tools, especially in frequent, low-stakes assessments or when paired with a few short answer questions. Fully auto-graded multiple-choice quizzes can function as “mastery” quizzes, in which a student has unlimited attempts but must get above a certain threshold (e.g., 90%, 100%) to move on. Using low-stakes, open-note practice tests can be an effective form of studying, and in many cases may be better for retrieval than students studying on their own.

You can also customize your Canvas quiz settings to control other conditions, such as time. Classic Quizzes and New Quizzes include options that add a layer of difficulty to repeatable multiple-choice assessments, such as time limits, shuffled questions or answer choices, and the use of question banks. These settings, when used with low-stakes assessments with multiple attempts, can help students practice meeting the course’s learning outcomes before larger summative assessments.

Versatility

Multiple-choice assessments sometimes get a bad reputation for being associated with rote memorization and lower order thinking skills, but in reality, they can be used to assess skills at every level of Bloom’s taxonomy. This includes higher order thinking skills, such as students’ ability to analyze a source, evaluate data, or make decisions in complex situations.

For example, you could present students with a poem or graph and then use a multiple-choice question to assess a student’s ability to analyze and interpret the example. Or, alternatively, you could create a question stem that includes a short scenario and then ask students to pick the best response or conclusion from the answer choices.

Examples of Multiple-Choice Items That Assess Higher Order Thinking Skills

Poem Analysis Example

[The poem is included here.]

The chief purpose of stanza 9 is to:

- A) Delay the ending to make the poem symmetrical.

- B) Give the reader a realistic picture of the return of the cavalry.

- C) Provide material for extending the simile of the bridge to a final point.

- D) Return the reader to the scene established in stanza 1.

(Answer: D)

This item tests higher order thinking skills because it requires test-takers to apply what they know about literary devices and analyze a poem in order to discriminate the best answer.

Source: Burton, S. J., et al. (2001). How to Prepare Better Multiple Choice Test Items: Guidelines for University Faculty.

Graph Analysis Example

The graph above illustrates the change in heart rate over time for two different groups that were administered a drug for a clinical study. After studying the graph, a student concluded that there was a large increase in heart rate around the one-minute mark, even though the results of the study determined that patients' heart rates remained relatively stable over the duration of five minutes. Which aspect of the graph most likely misled the student when they drew their conclusion?

- A) The baseline for y-axis starts at 70 beats/min, rather than 0 beats/min.

- B) The y-axis is in beats/min, rather than beats/hour.

- C) The graph lacks a proper title.

- D) The graph includes datasets from two groups, instead of just one.

(Answer: A)

This item tests higher order thinking skills because it requires test-takers to analyze a graph and evaluate which answer choice might lead someone to draw a misleading conclusion from the graph.

Source: In, J. & Lee, S. (2017) Statistical data presentation. Korean J Anesthesiol, 70 (3): 267–276.

Patient Scenario Example

A nurse is making a home visit to a 75-year old male client who has had Parkinson's disease for the past five years. Which finding has the greatest implication on the patient's care?

- A) The client's wife tells the nurse that the grandchildren have not been able to visit for over a month.

- B) The nurse notes that there are numerous throw rugs throughout the client's home.

- C) The client has a towel wrapped around his neck that the wife uses to wipe her husband's face.

- D) The client is sitting in an armchair, and the nurse notes that he is gripping the arms of the chair.

(Answer: B)

This item tests higher order thinking skills because it requires test-takers to apply what they know about Parkinson's disease and then evaluate the answer choices to determine which observation is the most relevant to the patient's care in the scenario.

Source: Morrison, S. and Free, K. W. (2001). Writing multiple-choice test items that promote and measure critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 40 (1), 17-24.

Multiple-choice questions can also be adjusted for difficulty by tweaking the homogeneity of the answer choices. In other words, the more similar the distractors are to the correct answer, the more difficult the multiple-choice question will be. When selecting distractors, pick answer choices that seem appropriately plausible for the skill level of students in your course, such as common student misconceptions. Using appropriately difficult distractors will help increase your assessments’ reliability.

Despite this versatility, there are still some skills — such as students’ ability to explain a concept, display their thought process, or perform a task — that are difficult to assess with multiple-choice questions alone. In these cases, there are other forms of assessment that are better suited for these outcomes, whether it be through a written assignment, a presentation, or a project-based activity. Regardless of your discipline, there are likely some areas of your course that suit multiple-choice assessments better than others. The key is to implement multiple-choice assessments thoughtfully and intentionally with an emphasis on how this format can help students meet the course’s learning outcomes.

Making Multiple-Choice Assessments More Impactful

Once you have weighed the pros and cons of multiple-choice assessments and decided that this format fits your learning outcomes and assessment goals, there are some additional measures you can take to make your assessments more effective learning opportunities. By setting expectations and allowing space for practice, feedback, and reflection, you can help students get the most out of multiple-choice assessments.

Set Expectations for the Assessment

In line with the Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework, disclosing your expectations is important for student success. Either in the Canvas quiz description or verbally in class (or both), explain to students the multiple-choice assessment’s purpose, task, and criteria. For example, is the assessment a low-stakes practice activity, a high-stakes exam, or something in between? What topics and learning outcomes will the assessment cover? What should students expect in terms of the number/type of questions and a time limit, if there is one? Will students be allowed to retake any part of the assessment for partial or full credit? Clarifying these types of questions beforehand helps students understand the stakes and goal of the assessment so they can prepare accordingly.

Provide Opportunities for Practice and Feedback

To help reduce test-taking anxiety and aid with long-term retrieval, make sure to provide students with ample practice before high-stakes assessments. Try to use practice assessments to model the format and topics that will be addressed on major assessments. If you are using a certain platform to conduct your assessments, like Canvas quizzes or a textbook publisher, consider having students use that same platform for these practice assessments so they can feel comfortable using the technology in advance of major assessments as well.

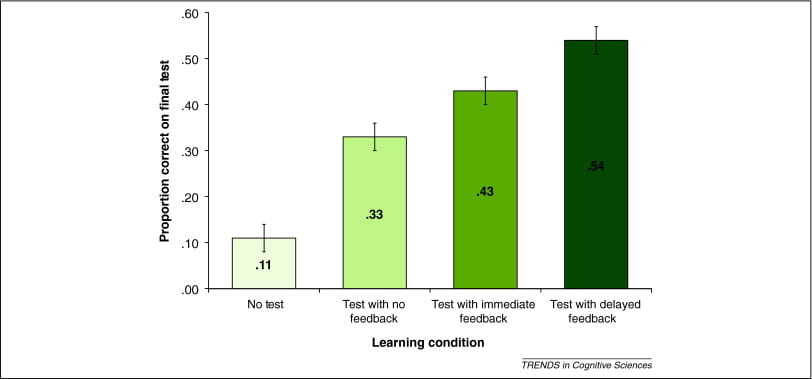

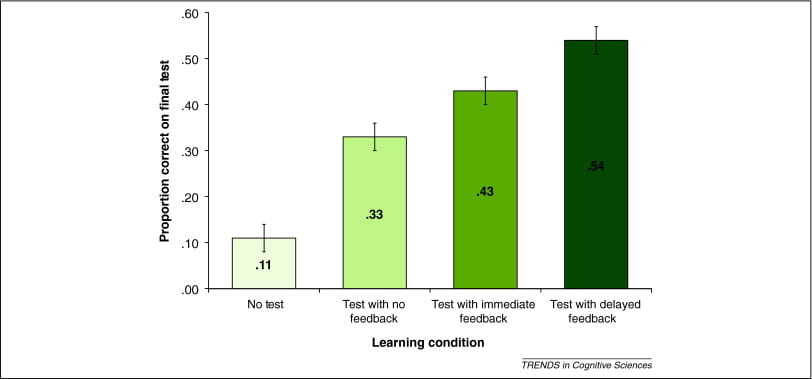

Research also indicates that providing feedback after an assessment is key for long-term retention. Interestingly, this is not only true for answers that students got wrong, but also in cases when a student arrives at the correct answer but with a low degree of confidence. Without assessment feedback, students may just check their quiz grade and move on, rather than taking the time to process their results and understand how they can improve.

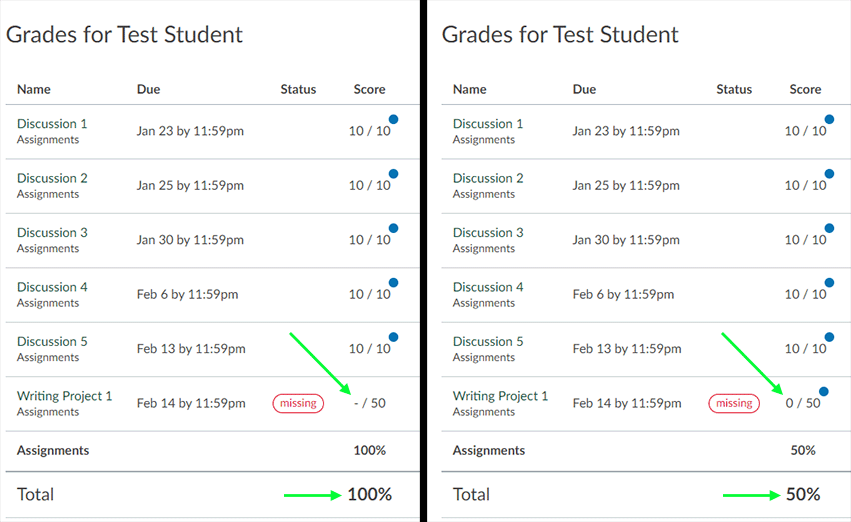

You can include immediate and automatic qualitative feedback for quiz questions through Canvas Classic Quizzes and New Quizzes. Feedback (or “answer comments”) can be added to individual answer options or to an entire multiple-choice item. For example, you can add a pre-formulated explanation underneath an answer choice on why that distractor is a common misconception. If a student has incorrectly selected that answer choice, they can read that feedback after submitting their quiz attempt to learn why their choice was incorrect.

Create Space for Reflection

Source: Roediger III, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention.

As indicated in the chart above, delayed feedback is potentially even more effective for long-term retention than immediate feedback. Consider reserving some time in class to debrief after important assessments and address students’ remaining questions. For asynchronous online courses, you could record a short post-test video in which you comment on trends you saw in students’ scores and clear up common misconceptions.

If you want to go a step further, you can also have students complete a self-reflective activity, also known as an exam wrapper, like a post-test survey or written reflection. Self-reflective activities like these have been shown to increase students’ overall performance in class by helping them learn how to reflect on their own study and performance habits, in addition to the positive effects on information retention mentioned earlier.

Questions?

Need some help designing your next multiple-choice assessment? Want to learn more about mastery quizzes, Canvas quiz settings, or exam wrappers? CATL is here to help! Reach out to us at CATL@uwgb.edu or schedule a consultation and we can help you brainstorm assessment solutions that fit your course’s needs. Or, if you’re ready to start building your assessment, check out this related guide for tips on writing more effective multiple-choice questions.

![]()