Writing good multiple-choice questions is challenging. Tricky or verbose questions can reduce the test item’s reliability and validity, while a poor selection of answer choices can make a question either far too easy or incredibly difficult. A question that suffers several common pitfalls might even work against the learning outcomes it is trying to measure. Fortunately, researchers and assessment experts have identified some common guidelines for creating more equitable and reliable multiple-choice assessments. In this guide, we’ll walk through seven tips for writing more effective multiple-choice test items.

The scope of this guide is focused specifically on authoring multiple-choice questions. If you’d like to dig into when to use multiple-choice assessments, as well as recommendations for scaffolding, testing in online environments, and providing feedback, check out this other CATL blog post on general considerations for creating impactful multiple-choice assessments.

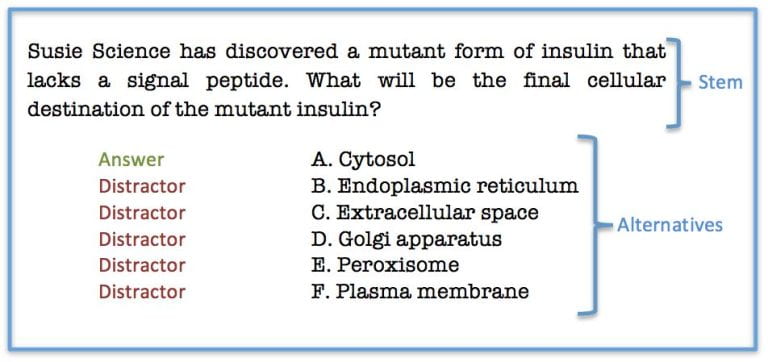

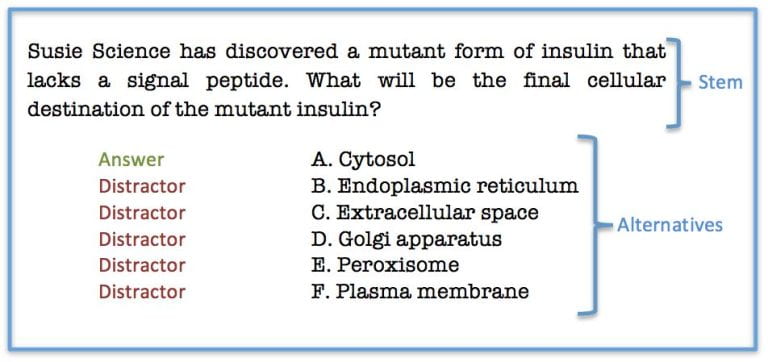

Before getting into the tips on writing questions, we’ll review the anatomy of a multiple-choice question and outline some common language that we use throughout this guide.

Table of Contents

The Anatomy of a Multiple-Choice Item

Throughout this article, we will use the following terms and definitions when referring to the parts of a multiple-choice question:

- Item: A question and its answer choices as a unit

- Stem: The posited question that respondents are asked to answer; often phrased as a question, but can also be a statement (e.g., fill in the blank)

- Alternatives: A list of suggested answers that appear after the question stem; comprised of several incorrect answer options and one (or more) correct or best answer(s)

- Distractor: An incorrect alternative

Example of a multiple-choice item, its stem, and the alternatives

Source: Vanderbilt Center for Teaching and Learning

Tips for Writing Effective Multiple-Choice Questions

Most of the recommendations in this guide have been adapted from How to Prepare Better Multiple-Choice Test Items: Guidelines for University Faculty Simple (Burton et al, 1991) and Developing and Validating Multiple-choice Test Items (Haladyna, 2004). We’ve distilled down these long-form documents into a few simple guidelines that align with current recommendations from experts at other centers for teaching and learning (see “Additional Resources”). If you are interested in learning more about the research behind these suggestions, we encourage you to check out one or both of the resources linked above.

Tip #1: Tie each item to a learning outcome

In order to maximize an assessment’s validity and reliability, each multiple-choice item should be clearly aligned with one of the assessment’s learning outcomes (and, by extension, the course learning outcomes). Generally, it is recommended to have each item tied to only one outcome each. However, in the case of items that assess higher order thinking and present complex problems or scenarios, it is possible that a multiple-choice item may assess more than one outcome.

Tip #2: Create a specific, clear, and succinct stem

A straightforward, clear, and concise stem free from extraneous information increases a multiple-choice item’s reliability. When writing and revising your question stems, it is a good practice to ask yourself if there is a simpler or more direct way to rephrase a question. Overly wordy stems rely on students’ reading comprehension, which is usually not one of the intended outcomes of the assessment. Likewise, confusing or ambiguous stems can be accidentally misleading. Ideally, a student who has mastered the target outcome should be able to answer the question posited even without the alternatives present.

Instead of this...

For millennia, humanity has been entranced by the ebb and flow of the tides. Many past civilizations believed the ocean's waters were controlled by monsters, spirits, or gods, but today know the scientific laws and theories that explain the tides. These movements are influenced by, in part, the gravitational force from the sun, the earth’s rotation, shoreline geography, and weather patterns, but all of these pale in comparison to the effects of:

- a) El Niño

- b) The gravitational force of the moon

- c) The ozone layer

- d) Deep-sea trenches

(Answer: B)

Why it doesn’t work: The extra information in the question stem makes it difficult for the test-taker to discern the question that is being posed. The question itself is also worded ambiguously.

Try this...

Earth’s tides are influenced primarily by:

- a) El Niño

- b) The gravitational force of the moon

- c) The ozone layer

- d) Deep-sea trenches

(Answer: B)

Why it works: The question stem has been revised to remove all unnecessary information and it now poses a simple, straightforward question.

Tip #3: Avoid using negatives in question phrasing

It is usually best to avoid negative phrasing in question stems, such as asking students to identify which alternative does not belong. Negatively phrased stems tend to be less reliable in assessing students’ learning than stems that ask students to identify the correct answer. The exception to this guideline is in cases when knowing what not to do is key, such as questions related to safety protocols. If you do choose to include a negative qualifier, use bold or italics to emphasize the negative word and make sure that you don’t create a double negative with any of the alternatives.

Instead of this...

Which of the following is not a quality of an active listener?

- a) Not talking over others

- b) Making eye contact with the speaker

- c) Asking clarifying questions

- d) Mentally planning a rebuttal while the other person is speaking

(Answer: D)

Why it doesn’t work: The question stem is phrased in the negative and the negative qualifier is not emphasized, making the question less reliable. Additionally, one of the alternatives also contains the word “not,” creating a double negative with the question stem.

Try this...

True or false? An active listener…

- Refrains from talking over others (T/F)

- Makes eye contact with the speaker (T/F)

- Asks clarifying questions (T/F)

- Mentally plans a rebuttal while the other person is speaking (T/F)

(Answers: T, T, T, F)

Why it works: This question stem has been rephrased to avoid using the word “not.” The answer choices have been turned into four separate true/false statements so each item can be assessed separately and have been revised to remove the word “not.”

Or consider this example...

Which of the following is not a recommended action to protect yourself during an earthquake if you are inside a building?

- a) Drop to your hands and knees

- b) Take shelter under a sturdy nearby desk or table

- c) Crawl to the nearest exit

- d) Cover your head and neck with your arms

(Answer: C)

Why it works: In this scenario, knowing what not to do during an earthquake is one of the learning outcomes, so it is appropriate to use a negative qualifier. The negative qualifier in the stem, “not,” has also been emphasized with bold and italics to draw attention to it.

Tip #4: Use plausible distractors

Good distractors need to appear plausible to students that have not met the target learning outcome, but not so tricky that they could be argued as correct answers by a test-taker that has met the learning outcome. When you are writing a multiple-choice question it is often useful to write the stem first, then the correct answer first. Once you have decided on these two pieces, formulate 2-4 distractors based on common student misconceptions. If you can’t think of another “good” distractor for a set of alternatives, it is usually better to have fewer alternatives than to include extra alternatives just for the sake of consistency.

Instead of this...

George Washington Carver is best known for his work as a(n) ______.

- a) Agricultural scientist

- b) Extraterrestrial expert

- c) Basket-weaver

- d) Juggler

(Answer: A)

Why it doesn’t work: The distractors are so absurd and far-removed from the topic of the question that even a student who knows nothing about George Washington Carver could discern the correct answer, making the test item neither reliable nor valid.

Try this...

George Washington Carver is best known for his work as a(n) ______.

- a) Agricultural scientist

- b) Electrical engineer

- c) Microbiologist

- d) Politician

(Answer: A)

Why it works: The distractors seem plausible, creating a question that will more accurately assess students’ knowledge of George Washington Carver.

Tip #5: Use homogeneous phrasing and formatting for alternatives

Small typos, inconsistencies in tenses or phrasing, or changes in text formatting can accidentally provide clues about which alternatives are the distractors and which are correct answers. Savvy test-takers can pick up on these inconsistencies and use this information to deduce the correct answer even if they have not achieved mastery for the desired outcome, so keep an eye out for these things as you proofread your exam. If you notice formatting inconsistencies in your Canvas quizzes, you can use the Rich Content Editor to remove all formatting and set the selected text to Canvas’s defaults.

Instead of this...

What three parts of speech can an adverb modify?

- a) Verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs

- b) Noun, adjective and preposition

- c) Verb, noun and conjunction

- d) Adjective, adverb and exclamation

(Answer: A)

Why it doesn’t work: Answer choice “A,” the correct answer, is in a different font from the other alternatives. Additionally, the distractors use the singular version of each part of speech, rather than the plural, and omit the Oxford comma before “and.” These inconsistencies hint to students that “A” is the odd one out.

Try this...

What three parts of speech can an adverb modify?

- a) Verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs

- b) Nouns, adjectives, and prepositions

- c) Verbs, nouns, and conjunctions

- d) Adjectives, adverbs, and exclamations

(Answer: A)

Why it works: The distractors have been revised to look consistent with the correct answer, creating a question that assesses students’ knowledge of parts of speech, rather than their eye for detail.

Tip #6: Avoid using none-of-the-above or all-of-the-above as alternatives

Questions that provide “all of the above” or “none of the above” as alternatives are generally less reliable for assessing outcomes than a multiple-choice question with mutually exclusive alternatives. The table below outlines the use cases for “all of the above” and “none of the above” along with why they are flawed for reliable assessment in each instance. If you can’t think of another distractor while drafting a question, remember that it is okay for some questions to have fewer alternatives.

Use of “all of the above” and “none of the above”

Alternative

|

Weakness

|

| “All of the above” as the answer |

Can be identified by noting that two of the other alternatives are correct |

| “All of the above” as a distractor |

Can be eliminated by noting that one of the other alternatives is incorrect |

| “None of the above” as the answer |

Measures the ability to recognize incorrect answers rather than correct answers |

| “None of the above” as a distractor |

Does not appear plausible to some students |

(Adapted from How to Prepare Better Multiple-Choice Test Items: Guidelines for University Faculty, Brigham Young University)

Tip #7: Create questions with only one correct alternative

Like none- or all-of-the-above alternatives, asking students to identify multiple correct alternatives is a less reliable form of assessment than an item with only one correct answer. Multiple-response questions are also reliant on confusing grading calculations, since selecting an incorrect alternative “cancels out” a correct selection (this Canvas guide goes into more detail about how Multiple Answer questions are auto-graded). And, in questions with more incorrect than correct answers, students can still score points by selecting no answers at all!

A straightforward multiple-choice item with only one correct answer and mutually exclusive alternatives is a more reliable way of discerning whether a student truly knows a concept or is guessing. Another option is to turn a multiple-answer question into a series of true/false questions, which will provide a more reliable picture of students’ understanding and a more valid grade for their efforts.

Instead of this...

Check all that apply. COVID-19:

- a) Is an infectious disease

- b) Is spread primarily through fungal spores

- c) Can be treated with antibiotics

- d) Can infect people of all ages

(Answer: A and D)

Why it doesn’t work: Because of the way multiple-response questions are graded, they are less reliable than individual multiple-choice or true/false questions.

Try this...

True or false? COVID-19:

- Is an infectious disease (T/F)

- Is spread primarily through fungal spores (T/F)

- Can be treated with antibiotics (T/F)

- Can infect people of all ages (T/F)

(Answers: T, F, F, T)

Why it works: Each statement is assessed individually, allowing for more granular and accurate scoring.

Questions?

Want more tips for writing multiple-choice questions? Looking for someone to help brainstorm outcome-aligned questions with? CATL is here for you! Reach out any time to set up a meeting or send us your questions at CATL@uwgb.edu.

Additional Resources