Article by Tara DaPra, CATL Instructional Development Consultant & Associate Teaching Professor of English & Writing Foundations

I went to the OPID conference in April to learn from colleagues across the Universities of Wisconsin who know much more than I do about Generative AI. I was looking for answers, for insight, and maybe for a sense that it’s all going to be okay.

I picked up a few small ideas. One group of presenters disclosed that AI had revised their PowerPoint slides for concision, something that, let’s be honest, most presentations could benefit from. Bryan Kopp, an English professor at UW-La Crosse, opened his presentation “AI & Social Inequity” by plainly stating that discussions of AI are discussions of power. He went on to describe his senior seminar that explored these social dynamics and offered the reassurance that we can figure this thing out with our students.

I also heard a lot of noise: AI is changing everything! Students are already using it! Other students are scared, so you have to give them permission. But don’t make them use it, which means after learning how to teach it, and teaching them how to use it, you must also create an alternate assessment. And you have to use it, too! But you can’t use it to grade or write LORs or in any way compromise FERPA. Most of all, don’t wait! You’re already sooo behind!

In sum: AI is everywhere. It’s in your car, inside the house, in your pocket. And (I think?) it’s coming for your refrigerator and your grocery shopping.

I left the conference with a familiar ache behind my right shoulder blade. This is the place where stress lives in my body, the place of “you really must” and “have to.” And my body is resisting.

I am not an early adopter. I let the first gen of any new tech tool come and go, waiting for the bugs to be worked out, to see if it will survive the Hype Cycle. This year, my syllabus policy on AI essentially read, “I don’t know how to use this thing, so please just don’t.” Though, in my defense, the fact that I even had a policy on Generative AI might actually make me an early adopter, since a recent national survey of provosts found only 20% were at the helm of institutions with formal, published policy on the use of AI.

So I still don’t have very many answers, but I am remembering to breathe through my resistance, which has helped me develop a few questions: How can I break down this big scary thing into smaller pieces? How might I approach these tools with a sense of play? How can I experiment in the classroom with students? How can I help them understand the limitations of AI and the essential nature of their human brains, their human voices?

To those ends, I’d like to hear from you. Send me your anxieties, your moral outrage, your wildest hopes and dreams. What have you been puzzling over this year? Have you found small ways to use Generative AI in your teaching or writing? Have your ethical questions shifted or deepened? And should I worry that maybe, in about two hundred years, AI is going to destroy us all?

This summer and next year, CATL will publish additional materials and blog posts exploring Generative AI. CATL has already covered some of the “whats,” and will continue to do so, as AI changes rapidly. But, just as we understand that to motivate students, we must also talk about “the why,” we must make space for these questions ourselves. In the meantime, as I explore these questions, I’m leaning into human companionship, as members of my unit (Applied Writing & English) will read Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI by Ethan Mollick. We’re off contract this summer, so it’s not required, but, you know, we have to figure this out. So if we must, let’s at least do it over dinner.

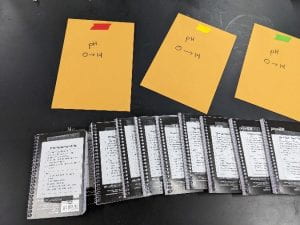

When Professor Lybbert began thinking about escape rooms, they were all the rage. She discovered an article in the Journal of Chemistry Education, which described, in detail, a Lab-Based Chemical Escape Room. The article describes a scenario in which four bombs are set to explode unless the chemists in the room are able to neutralize them. The scenario presented used the kinds of puzzles those familiar with escape rooms might be used to, but in order to solve these puzzles, chemistry knowledge would also come into play. This is what Professor Lybbert used as a guide to create her own physical escape room inside her classroom. More than just creating a fun activity, she created an environment designed to immerse her students in the escape room, complete with yellow caution tape, scary music, and a countdown timer. Her students get a full hour to work as a team to solve this puzzle.

When Professor Lybbert began thinking about escape rooms, they were all the rage. She discovered an article in the Journal of Chemistry Education, which described, in detail, a Lab-Based Chemical Escape Room. The article describes a scenario in which four bombs are set to explode unless the chemists in the room are able to neutralize them. The scenario presented used the kinds of puzzles those familiar with escape rooms might be used to, but in order to solve these puzzles, chemistry knowledge would also come into play. This is what Professor Lybbert used as a guide to create her own physical escape room inside her classroom. More than just creating a fun activity, she created an environment designed to immerse her students in the escape room, complete with yellow caution tape, scary music, and a countdown timer. Her students get a full hour to work as a team to solve this puzzle.

Students have the opportunity to use the knowledge they’ve gained throughout the course of the semester in a low-stakes (but heightened-intensity) lab activity that gives them the chance to reflect on their learning once the adrenaline has passed. Although not perfectly a real-world scenario, students do realize that they can use their knowledge when the time counts!

Students have the opportunity to use the knowledge they’ve gained throughout the course of the semester in a low-stakes (but heightened-intensity) lab activity that gives them the chance to reflect on their learning once the adrenaline has passed. Although not perfectly a real-world scenario, students do realize that they can use their knowledge when the time counts!

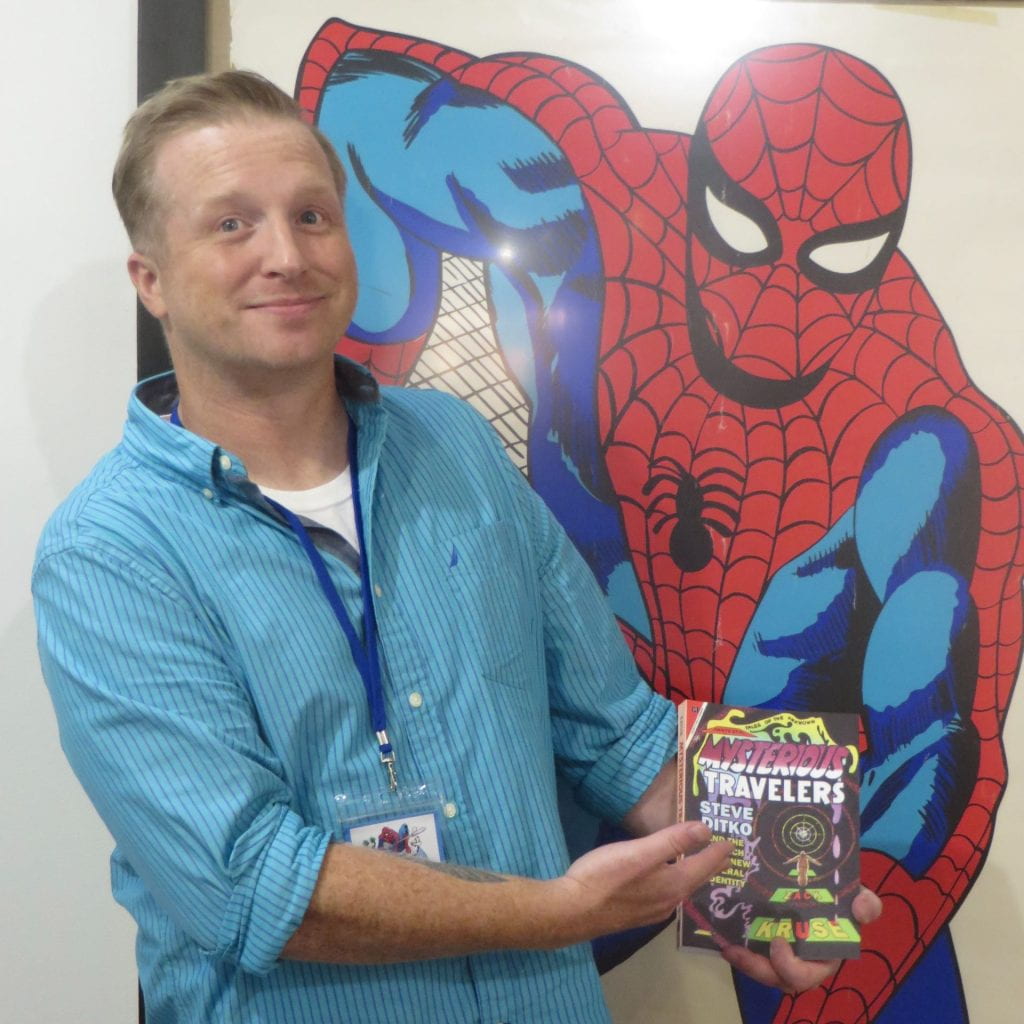

Professor Kruse has used the following comic books in his classroom. Some of those comic studies have included author visits. Professor Kruse uses a multitude of others not listed here and would be happy to offer recommendations if you’d like to integrate some of these works into your own classroom.

Professor Kruse has used the following comic books in his classroom. Some of those comic studies have included author visits. Professor Kruse uses a multitude of others not listed here and would be happy to offer recommendations if you’d like to integrate some of these works into your own classroom.