Assessments (Formative vs. Summative)

(Adapted from Carnegie Mellon’s: Design and Teach a Course)

Assessments should provide instructors and students with evidence of how well students have mastered the course objectives.

There are two major reasons for aligning assessments with learning objectives.

- Alignment increases the probability that we will provide students with the opportunities to learn and practice knowledge and skills that instructors will require students know in the objectives and in the assessments. (Teaching to the assessment is a good thing.)

- When instructors align assessments with objectives, students are more likely to translate “good grades” into “good learning.” Conversely, when instructors misalign assessments with objectives, students will focus on getting good grades on the assessments, rather than focusing on mastering the material that the instructor finds important.

Instructors may use different types of assessments to measure student proficiency of a learning objective. Moreover, instructors may use the same activity to measure different objectives (as I am doing with the alignment grid in this module). To ensure more accurate assessment of student proficiency, many instructional designers recommend that you use different kinds of activities so that students have multiple ways to practice and demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

Formative

The goal of formative assessment is to monitor student learning to provide ongoing feedback that can be used by instructors to improve their teaching and by students to improve their learning. More specifically, formative assessments:

- help students identify their strengths and weaknesses and target areas that need work

- help faculty recognize where students are struggling and address problems immediately

Formative assessments are generally low stakes, which means that they have low or no point value. Examples of formative assessments include asking students to:

- draw a concept map in class to represent their understanding of a topic

- submit one or two sentences identifying the main point of a lecture

- turn in a research proposal for early feedback

Summative

The goal of summative assessment is to evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional unit by comparing it against some standard or benchmark.

Summative assessments are often high stakes, which means that they have a high point value. Examples of summative assessments include:

- a midterm exam

- a final project

- a paper

- a senior recital

Information from summative assessments can be used formatively when students or faculty use it to guide their efforts and activities in subsequent courses.

Essential Statement for Your Course

Much of instructional design and online learning focuses on objectives which gauge student progress by measuring what students do. This is important because teachers ought to know the degree to which student mastery results from the instruction of the course. Yet, those objectives cannot get at the immeasurable benefits of learning that we hope students take from the course and transfer to their lives outside the classroom. Essential statements are where instructors articulate those big ideas which make the course meaningful for students and allow the course to live on in the minds of students long after they have forgotten many of the specific details they learned.

Essential statements work hand-in-hand with course objectives. The essential questions allow instructors to remain focused on the big important ideas of their disciplines even as the course objectives try to give a measurable shape to those big ideas. Essential statements help instructors answer the question: Why am I having students complete these objectives? While the objectives help instructors assess: How will I know that students grasped the essence of this course?

One way to think about the essential questions of a course is to ask: What do I want students to remember about the course five years from now? Students will probably not remember specific objectives, but hopefully they will remember some enduring question, such as:

- Whose perspective matters here?

- What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

- How does what we measure influence how we measure?

Resources

- What Makes a Question Essential? from Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

First Week of Class

As the first week of class draws nigh, instructors naturally turn their thoughts to those first moments that form a new community. These initial interactions offer instructors and learners an opportunity to set the tone for learning for the semester. We searched our library and reached out to UW-Green Bay faculty who have presented on their methods for building community and transparency in the first week to share their insights once again. Many thanks to Dr. Jenell Holstead for inspiring our objectives for the first day, and to Drs. Katia Levintova and Carly Kibbe for example icebreakers for building community in large lecture courses.

What are the objectives for the first day:

- Clarify all reasonable questions students might have about the course (course objectives, assignments, pre-requisites, when you’ll provide feedback, and how and when students should seek help); spotlight important parts of your syllabus and consider asking students to annotate the syllabus either before class or while you’re all meeting for the first time. Suggestions for how to do this are below.

- Build community and set the tone for the course environment with an introductory activity. Whether you’re teaching online or face-to-face, students are more likely to succeed when they have a greater sense of belonging not only to each other but also to the course design.

- Convince students of your competence to teach the course, predict the nature of your instruction, and know what is required of them (your expectations about performance in class). When appropriate, consider asking students to generate a class charter for participation so that they have a stake in shaping how and when they will be prepared to come to class. Giving your students some agency encourages them to hold themselves and their peers accountable for their preparedness.

- Give you an understanding of who is taking your course and what their expectations are and whatever you plan to do during the semester, do it on the first day. Some instructors ask students to do some “predicting” on the first day of class in order to gauge their expectations and learning goals. Suggestions for how to accomplish this are here.

Examples of Ice Breaker Activities

Examples of Ice Breaker Activities

- Sharing Course Trepidations.* Some students have high anxiety about beginning a new course, especially in some courses, such as math or writing, which may be associated with high student anxiety and expectations. Have your students pair up or work in groups to share some of their fears and concerns about starting your course. Groups can share with the larger class if they feel comfortable; this provides validation for the students and an opportunity for the instructor to address student concerns.

- Simple Self-Introductions.* Have students introduce themselves to the rest of the class, including their names, majors, and year in school. You can even have them include a “fun fact” about themselves. This also may help you remember them a little bit better. This is a particularly useful exercise in a course where student speaking, in the form of speeches, oral presentations, or regular discussions, are expected.

- Getting to Know Each Other through Writing.* Instead of asking students to interview one another verbally, have your students write down the information that is traditionally shared in an introduction. Students can write their names, majors, reasons for enrolling in your course, “fun facts” about themselves, etc. Have your students swap papers with one another and learn about their partners without speaking. This is especially useful in a writing-intensive course.

- The M&M Icebreaker. Each student should be given an M&M (or a Lifesaver, or other multicolored candy). They can be given this piece of candy either as they walk in to the room or while they are already sitting in their seats. Develop a few questions or ideas about what students can share with the rest of the class. Then ask the students to introduce themselves to either a small group of other students or to the whole class, depending on the size of your course. When they introduce themselves, what they share or say is dependent on the color of their piece of candy. For example, a red one might mean they share why they decided to take the course or what they did over the school break.

- Syllabus Icebreaker.* Before distributing syllabi, have students get into small groups (3-5 students depending on the size of your course) and introduce themselves to one another. In their groups, students write a list of questions they have about the class. After their questions are written down, hand out the syllabus and have the students find answers to their questions using the syllabus. This is not only an icebreaker, but can also show students that many of their questions can be answered by reading the syllabus. Afterward, the class “debriefs” as a large group and discusses any questions that were not answered in the syllabus.

- Syllabus Jigsaw.* Divide your syllabus into a few major sections. Have your students get into groups and distribute one major section to each group (for example, Group A gets “homework assignments”). Each group studies the section of the syllabus until they are confident about the information in it; groups then present that section of the syllabus to the rest of the class.

- Common Sense Inventory.* Make a list of true or false statements pertaining to content in your course (for example, in a Biology course, one might read, “Evolution is simply change over time”). Have students get into groups and decide whether each statement is true or false. As a large group, “debrief” by going over the answers and clarifying misconceptions.

- Anonymous Classroom Survey.* Write 2 or 3 open-ended questions pertaining to course content. Consider including at least one question that most students will be able to answer and at least one question that students will find challenging. Have your students respond anonymously on note cards; collect the answers to get a general sense of your students’ starting point.

- Choose your Thread:* ask students to read the poem “The Way It Is” by William Stafford, and reflect on what their “thread” is and how it sustains them.

- Draw* a picture or create a PowerPoint Slide where students can express why they are taking the class.

- Bingo: Make a 5×5 grid to use as a Bingo sheet. In each box, write a “fun fact,” or something that at least one of your students will probably relate to. Some examples might be: has traveled to Europe; plays a sport; is left-handed, but they can also be related to your discipline. Have your students walk around and talk to others until they find matches; the first to find all of them “wins.”

- Shoes Activity: This activity comes from Dr. Katia Levintova, which she uses in a large lecture class to develop community on the first day. Take a look to see how students’ shoes, a few minutes of silence, and shuffling groups helps her to do this.

(* = suitable for Online or Face-to-Face environments)

Why do an Ice Breaker?

Research around the first weeks of a course indicates that it is not just content expertise that matters to student experience and learning: it is also the environment that the instructor creates–ideally engaging students as active participants (Deluse, 310-312). First impressions are important—from the first time you greet your students to the built or virtual environments in which you teach. Sara Rose Cavanagh shows how students’ first impressions heavily influence their evaluation of courses at the end of the semester. (Cavanagh, 63)

Email CATL@uwgb.edu if you have an activity for the first week that you would like to share!

Resources

“!2 Icebreakers for the College Classroom” Center for Advancement of Teaching, Ohio State University

Angelo, T. A., and Cross, K. P. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. (2nd ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Cavanagh, Sarah Rose. The Spark of Learning: Energizing the College Classroom with the Science of Emotion. First edition. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 1. Morgantown, West Virginia: West Virginia University Press, 2016. [E-book requires UWGB login]

Deluse, Stephanie. “First Impressions: Using a Flexible First Day Activity to Enhance Student Learning and Classroom Management.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 30, no. 2 (2018): 308–21.

“First Day of Class – Design & Teach a Course.” Carnegie Mellon University. Teaching Excellence & Education Innovation – Eberly Center, 2019. https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/firstday.html.

“First Day of Class Guide.” Vanderbilt University. Center for Teaching, 2010. https://wp0.vanderbilt.edu/cft/guides-sub-pages/first-day-of-class/.

Holstead, Jenell. “Do’s and Don’ts for the First Day of Class.” Presentation Session presented at the Instructional Development Institute, University of Wisconsin – Green Bay, January 17, 2018. https://blog.uwgb.edu/catl/files/2018/01/DosDonts.pdf.

Jaggars, Shanna Smith, and Di Xu. “How Do Online Course Design Features Influence Student Performance?” Computers & Education 95 (April 2016): 270–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.014.

Kibbe, Carly, and Katia Levintova. “Building Community in Large Lecture Classes.” University of Wisconsin – Green Bay, January 28, 2018.

Samudra, Preeti G., Inah Min, Kai S. Cortina, and Kevin F. Miller. “No Second Chance to Make a First Impression: The ‘Thin‐Slice’ Effect on Instructor Ratings and Learning Outcomes in Higher Education.” Journal of Educational Measurement 53, no. 3 (2016): 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12116.

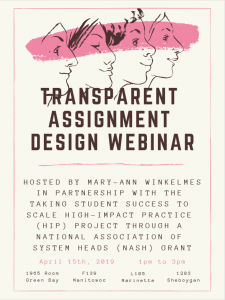

Event Follow-Up: Transparent Assignment Design (Apr. 15, 2019)

Faculty and staff from Green Bay, Manitowoc, Marinette, and Sheboygan joined other institutions participating in the Taking Student Success to Scale high-impact practice (HIP) project in an interactive webinar about designing transparent assignments. The session was hosted by Mary-Ann Winkelmes on 4/15/19. More information on Dr. Winkelmes’s work can be found beneath the embedded video.

Session Recording (4/15/19)

Session Resources

More Information

The National Association of System Heads (NASH) sponsored a webinar with Mary-Ann Winkelmes on Transparent Assignment Design. All members of the campus community were invited. Mary-Ann is the founder and director of the Transparency in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education Project (TILT Higher Ed).

Transparent instruction is an inclusive, equitable teaching practice that can enhance High Impact Practices by making learning processes explicit and promoting student success equitably. A 2016 AAC&U study (Winkelmes et al.) identifies transparent assignment design as a small, easily replicable teaching intervention that significantly enhances students’ success, with greater gains by historically underserved students. A 2018 study suggests those benefits can boost students’ retention rates for up to two years. In this session we reviewed the findings and examined some sample assignments. Then we applied the research to revising some class activities and assignments. Participants left with a draft assignment or activity for one of their courses, and a concise set of strategies for designing transparent assignments that promote students’ learning equitably.