This semester CATL partnered with staff and faculty in the First Nations Studies (FNS) program to bring you a series of events and resources on how to better support our Native students. Often after these types of events, attendees feel moved and invigorated to help affect change, but are at a loss for where to begin. While we recognize that there is no easy checklist to follow for becoming a better ally, we have collected some suggestions made by First Nations students, staff, and faculty during these events in the hopes that it might give you a starting place.

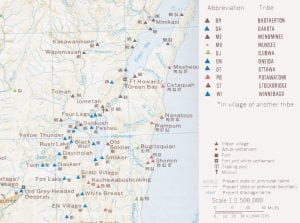

Please note that throughout this post we use the terms “First Nations”, “Native”, and “American Indian” interchangeably to refer to those who identify with any of the 574 federally recognized Tribal Nations in the United States, as all three terms are used in scholarly writing on First Nations topics.

Changes to Advocate for at an Institutional Level

Smudging, a regular and recurring part of many Native individuals’ religious practices, involves burning sacred plants to create smoke and is often conducted in living spaces to remove negative energy. To smudge in UWGB student housing, students must fill out a form and submit it to Residence Life at least one week in advance each time they smudge, as well as meet with a Residence Life staff member after submitting the form to discuss the location where the smudging will take place and receive fire extinguisher training. Some have likened our current smudging policy to requiring a week’s notice in advance every time one wishes to pray.

Our current policy also lack transparency both in the protocols students are expected to follow and in the religious protections students are provided. As a result, many First Nations students have reported feeling scared to smudge for fear of getting in trouble. In some cases, students have even had their dorms searched by campus police after smudging due to misinformed reports of smoke or odors. UW-Superior's smudging policy provides an example of a much more robust and accommodating policy at another UW institution that we could borrow from as we consider reforming our own policy.

Our First Nations students cite the Center as one of the most important support systems during their time at UWGB, as it is one of the best ways for them to connect with staff and faculty that are also of a Native background. For non-native students, staff, and faculty, the Center is also a great educational resource, and yet, many are still unaware of its existence. If the university hired a full-time staff to manage the Center’s resources and educational materials, we could expand and refine our collection to make it an even better resource for research and education.

Recently the photos of alumni that hung in Mary Ann Cofrin Hall were replaced with photos of new individuals. Among those original photos were two particularly important Native figures from our community—William Gollnick, who served as Oneida Chief of Staff from 2006–2011, and the late Maria Hinton, an Oneida Tribal Elder. Many in the FNS program have expressed that they wish for these photos to be tracked down and either hung in a new location or turned over to the Education Center for First Nations Studies so they can display them.

The inclusion of Native faculty and staff at a predominantly white institution (PWI) helps break down longstanding stereotypes about Native peoples, especially when their presence is seen and felt in a variety of professional areas. As highlighted in the introduction of Beyond the Asterisk, Native faculty and staff are also key to Native student success, especially at PWIs. It is important to our students that they can see themselves reflected in the faculty and staff they interact with on a daily basis. As a non-native ally, continue to support the First Nations faculty and staff around you and encourage our institution to continue hiring Native individuals in a variety of positions and departments.

Changes You Can Implement Personally

In 2018, First Nations faculty at UWGB created our university’s own land acknowledgment statement. Including the land acknowledgment in your teaching or other practices is a way to help First Nations students feel seen and acknowledged. If you’d like to learn more about the land acknowledgment, we encourage you to watch this roundtable panel on the topic from the 2021 Instructional Development Institute and then read this blog post for follow up resources and suggestions.

The university’s Education Center for First Nations Studies and the Intertribal Student Council promote many campus-wide or public events that create spaces for non-native students, staff, and faculty to learn about Indigenous cultures and form relationships with their Native colleagues and peers.

While students should feel welcome to share their own experiences or knowledge of First Nations topics, they should never feel pressured to do so just because of how they identify. Be careful not to single out a Native student or treat them as a “spokesperson” for people of their background or other Indigenous backgrounds; to do so is a form of tokenism.

Our Education Center for First Nations Studies, which has its own curated collection of resources, is a great place to look for educational materials for yourself or for your classroom. The Center also sponsors Elder Hours in which any member of the campus community can drop in during certain hours (either in-person at the Center or virtually via Zoom, depending on COVID guidelines) and meet with a local tribal elder. Stay tuned to see if Elder Hours will continue over Zoom or return to in-person for Fall 2021.

Wisconsin First Nations, created in collaboration between the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s American Indian Studies Program, PBS Wisconsin, and the UW-Madison's School of Education, is a site full of educational resources on Wisconsin American Indian studies. The Disproportionality Technical Assistance Network has also compiled a fantastic collection of articles, publications, media, and more on First Nations histories, cultures, stories, and educational practices. You can also consult our university’s First Nations Studies Library Guide for a collection of educational resources accessibility through the Cofrin Library.

Are there opportunities for you to include the work of First Nations authors, scientists, musicians, or artists in your content area? One example offered by a former student was to include the work of Native poets in an English course. Additionally, are there faculty in your field at a local tribal college that you could collaborate with or invite into your classroom as a speaker? Look for ways to meaningfully and intentionally include their voices and presence in your own work. The staff of the Education Center for First Nations Studies would be happy to assist you in finding those materials or making those connections.

Thank You

There is still much work to be done, but by working together on these initiatives we can make strides towards a more supportive and inclusive environment for our First Nations students. We welcome you to take these next steps with us as we make UW–Green Bay a better place for all to learn, grow, and succeed.

This post, the Beyond the Asterisk reading group, and the First Nations Students’ Perspectives of UW–Green Bay film showing and panel are a part of a larger series created in collaboration with the staff and faculty of the First Nations Studies program. View the series, titled Building Our Shared Stories Through First Nations Student Engagement, and a complete list of events here.