Post by Crystal Lepscier and Sam Mahoney

Introduction: What is the Land Acknowledgment, Why Does It Matter?

As we reckon with our nation’s history of genocide and oppression of Indigenous peoples, it is growing increasingly common for institutions of higher learning to create a land acknowledgment statement. Our university’s own land acknowledgment recognizes that our institution lives on the sacred and ancestral land of the Menominee and the Ho-Chunk Nations, while also acknowledging the twelve First Nations that currently reside in Wisconsin. Its inclusion in university events and publications has become a small but important step in increasing the visibility of the First Nations peoples that have lived and continue to live in this area. As the act of land acknowledgment becomes more routine, the danger is that, with time, it may begin to lose its impact. How then might we avoid turning land acknowledgment into a rote task that undermines the gravity of its intent?

Consider the land acknowledgment to be the first stepping stone on a path to becoming better allies as non-Natives. In order to truly, meaningfully engage with it, we must continue to educate ourselves on First Nations history and cultures, engage with First Nations stories in historical and modern contexts, and apply this knowledge in actionable tasks that honor First Nations people. In this post, we’ve compiled a list of suggested next steps you might take and resources to explore as you build on the land acknowledgment.

Next Steps: Forming A Foundational Knowledge of First Nations History

As non-Natives, it is necessary that we educate ourselves on the history of Indigenous peoples in the Americas. First, if you haven’t already, we encourage you to familiarize yourself with the UW–Green Bay Land Acknowledgment. Challenge yourself to go beyond simply reading the statement, and instead take the time to learn the names of the First Nations communities that were and continue to be affected by colonialism in Wisconsin.

We must also understand that First Nations’ connection to the land goes much deeper than the physical space—there also is profound ancestral and spiritual significance. Gregory Cajete, Director of Native American Studies at the University of New Mexico, eloquently explains: “It is this place that holds our memories and the bones of our people… this is the place that made us.” The land acknowledgement is as much about the connection between people and land as it is about their geography.

Going further, contemplate the Doctrine of Discovery, a principle of international law created by the Pope in the 15th century that was used to justify the dehumanization of the original inhabitants of the Americas and rationalize the violence committed against those peoples by European colonizers. Note how the ramifications of this philosophy are still seen and felt in our nation’s educational, legal, and economic systems today.

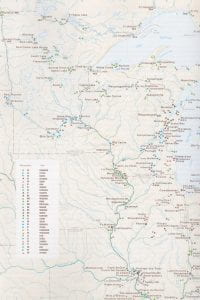

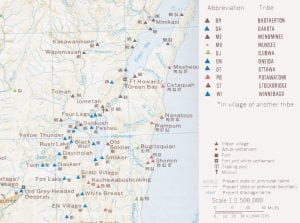

As you educate yourself on Indigenous history, we encourage you to engage with the session recording from the land acknowledgment session at the Instructional Development Institute this year. Among other resources, this presentation contains a collection of historical maps that illustrate the effects of colonization on the distribution, population, and land occupancy of First Nation peoples. Additionally, The Ways has a map of treaty lands, tribal lands, and Native populations in Wisconsin and surrounding regions, along with some important background information on the displacement of various Native peoples. On a global scale, Native Land Digital has created an extensive, interactive world map to explore the geographic approximations of Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties.

Going Deeper: Actively Engaging with First Nations Stories

For those of us who are non-Native, it is also our role to listen to the stories of First Nations peoples and learn from them. The Ways, mentioned in the previous section, is an online publication by PBS Wisconsin Education which promotes stories about contemporary First Nations cultures and languages. Likewise, Wisconsin First Nations is a fantastic collection of teaching resources on American Indian studies in Wisconsin, created as a collaboration between the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, PBS Wisconsin, UW-Madison’s School of Education.

Consider also investigating the university’s First Nations Studies Library Guide for a selection of books, websites, databases, and films both for use in the classroom and your own personal education. One recommended title to check out or purchase is Indian Nations of Wisconsin by Patty Loew, a comprehensive text on the struggles and perseverance of the Tribal Nations of Wisconsin. J P Leary, one of our own faculty members in the First Nation Studies program, authored one of the book’s two forwards.

Application: Respectively Honoring First Nations People

Expand the sections below for strategies for building upon the land acknowledgement to honor First Nations.

Did you know that our university has an Education Center for First Nations Studies, located in Wood Hall 410? Besides providing an overview of the First Nation Studies (FNS) programs at UWGB, you will also find resources on the languages, educational philosophies, teachings, and cultures of some of Wisconsin’s First Nations communities. When you have the chance, introduce yourself to some of our FNS faculty and staff, as well as the tribal Elders that partner with our FNS program. Be receptive to opportunities to collaborate and reach out to them if you have ideas.

Beyond that, think about how you might engage with our Indigenous communities outside of our university. Perhaps there are faculty at a Tribal College or University that would be interested in partnering in collaborative research or program development in your field—the College of Menominee Nation, for example, has a campus right in Green Bay. You might consider reaching out to other First Nations organizations and nonprofits in our community as well. Our Education Center for First Nation Studies is here as resource if you need guidance on where to look.

Another way to be an ally is to engage in events and programs that honor the First Nations of Wisconsin and further public education on their cultures and histories. For starters, try celebrating Indigenous People’s Day on October 12 and encourage your students to do the same. Last year as a part of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, the university released a short video where several students and faculty share what Indigenous People’s Day means to them. We also honored our First Nations by installing a land acknowledgment display in the Student Union, which showcases the flags of each Tribal Nation and a plaque with our university’s land acknowledgment statement.

You can also remind your students that November is Native American Heritage Month. Often the university and larger Green Bay area will have events during this month for students, faculty, and general community members that would be worth checking out.

Additionally, some of the faculty in the First Nation Studies program are partnering with CATL to bring you a series of events centered on supporting our First Nations students. Be on the lookout for more information about our upcoming reading group for Beyond the Asterisk, a showing of a FNS student film later this spring semester, and a larger workshop in the works for Fall 2021.

It is important that land acknowledgment is not an afterthought, but a meaningful part of your pedagogy as well. Perhaps include a short personal statement before the UWGB Land Acknowledgment in your syllabus in which you explain what it is and why you feel it’s important to include. If your class meets synchronously, consider making space on the first day of class to verbally honor the land acknowledgment as well. One suggestion by Dr. Carol Cornelius, one of our resident Elders, is to challenge ourselves as instructors to learn something new about one of the twelve First Nations of Wisconsin each semester. Then, when you include the land acknowledgment in your syllabus or discuss it in your course, you can make it more personal by highlighting that specific people’s individual culture and history.

Conclusion: Continuing the Conversation

It would be impossible to compile a definitive list of resources and actionable tasks to build on the land acknowledgment, so see this blog post as just the beginning. As you explore and reflect on these resources, we encourage you once again to utilize our campus’s Education Center for First Nations Studies, including their curated, continuously evolving collection of materials by and about First Nations peoples. They also sponsor Elder hours, held via Zoom this semester, in which students, staff, and faculty can drop in and talk with Napos, a Menominee tribal elder and our Oral Scholar in Residence. Do you have other ideas for ways you might continue engaging with the land acknowledgment and the histories, cultures, and peoples of Wisconsin’s First Nations? Let us know in the comments below, or by emailing catl@uwgb.edu.

About Crystal Lepscier

Crystal Lepscier (Little Shell/Menominee/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the First Nations Student Success Coordinator and an Associate Lecturer for the First Nations Studies program here at UW–Green Bay. As a student success coordinator, Crystal works to build partnerships with Wisconsin First Nations communities in order to increase UWGB’s recruitment and retention of First Nations students, provides those students with additional support through academic advisement and counseling, and contributes to programming on First Nations history and cultures. Crystal is also currently pursuing her EdD in First Nations Education at UWGB and will be among the first cohort of students to graduate from the program in 2022.

Crystal Lepscier (Little Shell/Menominee/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the First Nations Student Success Coordinator and an Associate Lecturer for the First Nations Studies program here at UW–Green Bay. As a student success coordinator, Crystal works to build partnerships with Wisconsin First Nations communities in order to increase UWGB’s recruitment and retention of First Nations students, provides those students with additional support through academic advisement and counseling, and contributes to programming on First Nations history and cultures. Crystal is also currently pursuing her EdD in First Nations Education at UWGB and will be among the first cohort of students to graduate from the program in 2022.