A Portrait of Grief and Courage: Hmong Oral Histories and Folktales, by Sandra Shackelford, with translations by May Lee Lor and transcriptions by Ma Le Lor, is now on sale. Click this link for purchase and pick up information.

Interviewer’s note: Sandra’s written responses have been edited to include further details and quotes that she provided during our verbal interview. Interviewer’s notes have been marked in brackets. All other words, while occasionally adjusted for flow, are Sandra’s own.

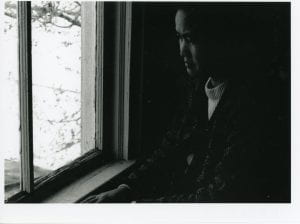

Sandra Shackelford, 1991.

You’ve been fighting for civil rights for decades — a battle that continues even now. What drew you, a white woman from Green Bay, Wisconsin, toward amplifying marginalized voices?

I was a junior in the Academy, an all-girl high school in Green Bay. I was popular. I was invited to so many dances and proms I ran out of space filling up my many dance cards. What I wasn’t was your standard “smart.” I hadn’t been able to read until the seventh grade. [Interviewer’s note: At the behest of her trained ballerina and cosmetologist mother, Sandra’s early education lay primarily in the performing arts — dancing and singing — for which she received both acclaim and the disapproval of the nuns at her Catholic school.] Later on in my educational sojourn, I had a surprise.

That’s when my Latin teacher called me aside after class. I expected to be reprimanded for something.

Instead, she said this: “Sandra, you’re not very bright, but you’ve got a nice personality. I know a place that could use a girl like you.”

My life changed forever.

I climbed aboard a train and went to that place where I could be used: Greenwood, Mississippi, the home of the White Citizens’ Council. The place I went to was St. Francis Center, where Black and White female members of Pax Christi Secular Institute lived and worked in the segregated interior of the city known for its production of cotton — picked, of course, by indentured Black citizens. I spent the summer [there] between my junior and senior year in high school. I taught Bible School and helped separate and organize medicines in our dispensary.

Going to Mississippi showed me a way of life that I preferred.

When I returned to school and began my senior year, the nuns’ take on me had changed dramatically. When I graduated in 1958, I was given the Lumen Award for my work over the summer.

Sandra Shackelford, 2023.

After graduation, I returned to the Center, and for the next 11 years, I dedicated myself — my life — to the work of Pax Christi and the Franciscan mission of “sowing love.” After reading a book on Maria Montessori’s method of teaching, I started and conducted a kindergarten, drawing in children from around our segregated neighborhood. Another Center member and I started a weekly newspaper, The Center LIGHT, which printed the news concerning the Black community.

The paper’s printed and defining intention — to “give people the light and they will find the way“ — roused the ire of the Ku Klux Klan. One night, a truck drove into our parking lot and hurled a firebomb, hoping to destroy our efforts to serve as the voice encouraging and celebrating racial equality. Unfortunately, the scars embedded themselves in the building’s exterior but also in my heart.

I returned to Green Bay at the Age of Aquarius, suffering from what no one else could see — a broken heart and the lingering effects of PTSD.

Fortunately, in the 1990s, I connected with Northeastern Wisconsin Technical College and its Family Support Program and my friends, May Lee Lor and Ma Lee Lor. Being led into the lives of the Hmong and the sharing of their life stories [about] the terror they experienced in their fight for survival helped heal the wounds I’ve carried with me after witnessing inhumanity in the racist South.

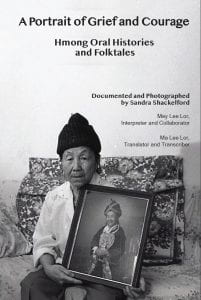

A Portrait of Grief and Courage: Hmong Oral Histories and Folktales, by Sandra Shackelford

What was your journey like to put A Portrait of Grief and Courage together?

I began working with the Hmong refugees in the 1990s when I was hired by Northeastern Wisconsin Technical College to work in their Family Support Project. Hmong refugees had recently begun arriving in Brown County. At the time I knew little about our new residents, but fortunately, I’d soon learn from two experts who became dear friends, May Lee Lor and Ma Lee Lor. May Lee served as my translator as we went from home to home working for NWTC’s program intending to meet the needs of the traumatized victims of the Vietnam War.

We went from house to house (or apartment) in an effort to help them adapt to a new type of life and culture. Later, once we’d concluded in these efforts, we connected with Ma Lee, seeking her help translating and transcribing the oral histories of several refugees May Lee and I had recorded on tape.

Our collaboration, along with the help of many others — including Debra Anderson, the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay archivist and Rebecca Meacham, English professor and director of UW-GB’s BFA in Writing and Applied Arts, led to the publication of this book, A Portrait of Grief and Courage.

Pa Lee, a Hmong refugee in Green Bay, WI. Photographed by Sandra Shackelford

What were your biggest takeaways from speaking with the Hmong people whose stories and images are compiled in A Portrait of Grief and Courage? Did any one story stick with you in particular?

Putting together this oral history of newly arrived Hmong refugees was an experience that will stay with me through my life. Meeting people of courage, human beings who survived unimaginable trauma — witnessing the death of friends and loved ones, the destruction of their homes and villages – documenting these experiences will stay with me throughout my life. Their spoken stories not only taught me what courage looks like, and is, but [also] served as a long-needed healing balm for my own leftover depression.

Why does storytelling matter to you?

I believe in voice. What you’re doing is talking to the reader and making a personal connection by telling the story of your life and encourag[ing] them to do the same thing… To find those kinds of people that will help you believe in yourself… they certainly changed my life.

I really found my home helping other people who experienced violence and that kind of thing — sexism — speak their truth by writing their stories… I started out teaching women [in writing circles, later expanding to other groups], but — helping people overcome their traumas and finding value in their lives by helping them write their truths, speak their truths.

I’ve read Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” and the feminine equivalent, the “Heroine’s Journey,” and that’s what we go through [in] our lives. Our lives are our story. However graphically we tell it, we just need to get it out[…] We listen and learn from other people’s stories.

If APoGaC found its way into the hands of any one person, who would you like to read it most?

A Portrait of Grief and Courage is a book everyone should — and hopefully will — read. These heartrending accounts could educate and expand their thinking and help them see and value the connection as members of the same fragile and precious human family.

It is my deepest hope that this book will connect readers, [and] that in learning to respect and love one another, we will be able to find peace as individuals and as a common and shared humanity.

A Portrait of Grief and Courage: Hmong Oral Histories and Folktales, by Sandra Shackelford, with translations by May Lee Lor and transcriptions by Ma Lee Lor, is now on sale. Click this link for purchase and pick up information.

Leave a Reply