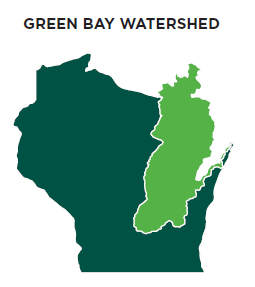

Many people may not realize it, but Green Bay is the world’s largest freshwater estuary, a semi-enclosed area in the Great Lakes where lake water and water from rivers and streams meet. The University of Wisconsin-Green Bay hopes its unique location will help it secure a National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) designation.

Becoming a NERR would provide more resources to address problems in Green Bay and Lake Michigan, including changing water levels, algae blooms, flooding and coastal erosion.

UW-Green Bay is leading the process to have Green Bay declared a NERR. Nationwide, there are 29 coastal sites, including the Great Lakes, designed to protect and study estuaries and their coastal wetlands. There are two on the Great Lakes, including one on Lake Superior, which is managed by UW-Madison’s Extension Division.

“The NERR designation isn’t just for the University or Green Bay. It’s something that will benefit the entire region,” said Emily Tyner, UW-Green Bay’s Director of Freshwater Strategy. “Hosting the NERR could enable new initiatives in the region by leveraging nationwide programs.”

She added becoming a NERR doesn’t preclude existing water uses or come with any additional regulations. Sites for the NERR also will be on publicly owned land so no additional property will need to be purchased.

Water plays a critical role in Wisconsin’s economy since it’s bordered by water on three sides, said Matt Dornbush, Dean of the Austin E. Cofrin School of Business at UW-Green Bay. Dornbush, who was a scientist before moving into college administration, was associate provost when the project began and is still engaged with it.

“Water resources play an increasing role in the viability of the state’s economy,” he said. “Water is important in the local economy. In addition, people live here because of our water resources.”

Established through the Coastal Zone Management Act, the reserves are a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and coastal states. While NOAA provides funding and national guidance, each site is managed on a daily basis by a state agency or university with input from partners. Upon designation as a National Estuarine Research Reserve, UW-Green Bay will coordinate the management, restoration and protection of the Green Bay ecosystem. The NERR also includes research, education, stewardship and training operations.

Becoming a NERR is a lengthy process, but one that is worth it, Tyner said. UW-Green Bay is currently in step two of the six step process — the evaluation of potential sites. “Our goal is to finish the site selection process by 2022 with the management plan complete by 2024,” she said.

The designation process began in 2019 when Gov. Tony Evers submitted a letter of intent to NOAA for the bay of Green Bay to be chosen as a NERR location. Tyner and the University are spreading the word about the benefits of having the bay of Green Bay named a NERR location, as well as making clear that the designation won’t affect commercial or recreational activity in the bay.

“We need to educate the public and our stakeholders. That means doing a deliberate, thorough job of telling people what it’s about, making sure questions are answered and soliciting public input on what their vision for what the bay of Green Bay NERR can be,” Tyner said.

John Katers, dean of the College of Science, Engineering, and Technology, said having a NERR will attract more attention to the unique ecosystem in Green Bay’s backyard.

“The work being done will look at what we can do to make the ecosystem’s health improve,” he said. “It will definitely be a hub to bring researchers to the area. There will be basic research done, which is done at all NERRs, such as looking at water levels and temperature, but then there will be the opportunity for a lot of individual projects as well.”

The current stage of designation also includes the criteria for selecting a site and then determining possible sites. A final site is then nominated and sent to NOAA.

Besides time, it also will require funding support to bring the NERR to fruition. “A lot of fundraising will be necessary as we take different steps along the way, but once we receive the NERR designation, 70 percent of future funding will come from the federal government,” Tyner said. “We have a lot of partners we are working with.”

Dornbush said water resources in the region face issues that the NERR can address, such as invasive species, runoff and industrial use of water. “Complicated issues require a coordinated response,” he said.

UW-Green Bay has multiple factors in its favor for being named a NERR site. First, the University’s four campuses are all near the water and run the distance from the border with Upper Michigan south to Sheboygan. Secondly, water related research isn’t something new for UW-Green Bay.

“The University also has a long history of research, we’re also involved in the Cat Island Restoration plan and we did some of the foundational work for the Fox River cleanup,” Tyner said. “With our location, it’s important to be involved in freshwater research.”

A lot goes into the site selection, Katers said. “The NERR will not only have a visitor’s center that will attract attention and welcome visitors, but also labs where people can do their research,” he said.

Being named a NERR will attract more researchers to the region and “we’ll also obtain resources we might not have had before,” Dornbush said.

“It’s important for us to lead in areas important to the region and state, and water fits with that. Water is critically important to our region — that’s what brought people here,” he continued. “Water will become an increasingly important part of our future.”

SELECT RESEARCH SPONSORS

- Greater Milwaukee Foundation (Fund for Lake Michigan), National Estuarine Research Reserve, $150,000

- U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Green Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, $60,000

- Private funding through the UW-Green Bay Foundation