On Wednesday, Mar. 6, 2024, CATL teamed up with Assistant Professor of Humanities, Kristopher Purzycki, for a workshop on improving the accessibility of educational resources shared in courses and on campus. This session explored common accessibility pitfalls in crafting digital learning materials, covering tasks like creating and sharing PowerPoint presentations, PDFS, and Canvas elements such as media and syllabi. As a continuation of this workshop, we’ve complied practical accessibility tips and demonstrations for instructors to incorporate when creating learning materials.

Prioritizing Accessibility Matters for Student Success

Meeting certain accessibility standards is not just about compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act; it is also crucial for enhancing student success and engagement. Accessibility (specifically digital accessibility) proactively eliminates barriers during the design and creation phase of materials.

In cases where accessibility measures still pose challenges for learners, students can work with Student Accessibility Services (SAS) to seek formal accommodations and instructors will work with SAS to fulfill the accommodation request. Many students may not disclose their disabilities to their university or face other obstacles hindering them from receiving formal accommodation. Consequently, academic success often relies on students’ individual efforts and faculty commitment to accessible learning materials. While not proposing a complete overhaul of course materials, CATL hopes to promote simple steps to enhance the accessibility of educational learning materials, all in the pursuit of student success.

- Make course changes based on level of seriousness.

- Learn and adapt based on experiences and student feedback.

- Use the UWGB library as a resource to help refresh and update your class materials/readings.

- Use the Accessibility Checkers available to you in Microsoft Office (like Word, PowerPoint, Excel) and Canvas).

Canvas Accessibility Tools to Help Review Your Course

Expand the titles below to learn how to use the accessibility tools and checks available to you in Canvas.

How to Use the Canvas Accessibility Checker – Video Demo

Validate Links in Your Canvas Course – Video Demo

Note: This video is demonstration is from Arizona State University Learning Experience (LX) and displays their specific instance of Canvas. While UWGB’s Canvas may operate and look different, the validate course link application works the same. Need more? View the Instructor (Canvas) guide on Validating Links in Canvas.

Using the Canvas Course Accessibility Checker UDOIT – Video Overview

Learn even more with UWGB's Knowledgebase guide on using the UDOIT Cloud Accessibility tool to check your Canvas course accessibility.

Video Accessibility with Kaltura My Media and Automatic Closed Captions

Expand the titles below to learn how to upload your own course videos or YouTube finds to Kaltura My Media. This allows for automatic closed captioning, caption editing, and transcription addition for videos in your Canvas courses or those shared with students.

How to Upload Videos and Add Captions with Kaltura My Media – Video Demo

How to Embed Videos and Add Transcripts with Kaltura My Media – Video Demo

Tip: You can adjust the max embed size of your video under the Embed Settings option. Feel free to use this to adjust the size of your video display in your Canvas course.

PDF Accessibility with Adobe Acrobat – Optical Character Recognition (OCR) Scanning

Expand the title below to learn how to enhance the accessibility of your PDFs by using OCR scanning. While OCR scanning doesn’t guarantee full accessibility for assistive technologies like screen readers, Adobe Acrobat Pro offers additional tools to improve accessibility before sharing PDFs digitally.

How to Use OCR Scanning with Adobe Acrobat Pro for PDFs – Video Demo

Tip: Before creating your own PDF documents and PDF scans of readings, contact the UWGB library and ask if they already have a digital resource available.

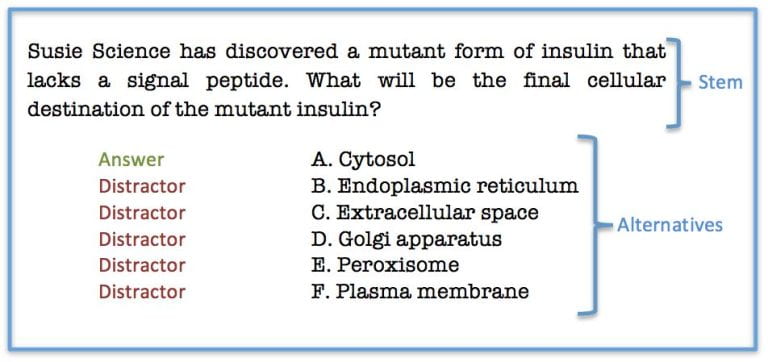

Image Accessibility and Informative Alt Text

Expand the title below to learn more about writing helpful alt text for images with specific examples, such as when you are creating your syllabus.

How to Add Alt Text in Microsoft Word and PowerPoint – Video Demo

A Note About Your Syllabus

Your syllabus is a great resource for our students and their first look into your class and learning environment. Because of this, your syllabus should include language that makes your desire for student success obvious. This can be done by incorporating course norms that encourage students to reach out to you if materials are not accessible for them. At UWGB instructors must include an “Accommodation Statement” on their syllabus. While not a requirement, instructors can show their commitment to accessibility and student success by including an additional accessibility statement. See an example of this type of Accessibility from Bates College below.

"Bates College is committed to creating a learning environment that meets the needs of its diverse student body. If you anticipate or experience any barriers to learning in this course, please feel welcome to discuss your concerns with me." – Bates College: Sample Syllabus Accessibility Statement

Learn More

If you’d like to learn more about accessibility, we encourage you to sign up for LITE 120, a self-paced training course that covers the basics of accessibility in Canvas, as well as SAS’s training course on creating accessible documents (i.e., with Word, PowerPoint, or PDF). Plus, check out CATL’s top 10 dos and don’ts of digital accessibility for even more resources.

Related Events and Opportunities

Join us as we conclude this semester’s workshop series with a session on “Using Universal Design for Learning (UDL)to Increase Access” led by the director of UW-Green Bay’s Student Accessibility Services, Lynn Niemi, and Art and Design Professor, Alison Gates. Attendees will continue the conversation about neurodiversity and explore how to use UDL to remove barriers in course materials and increase student access. This workshop will be held virtually via Zoom on Apr. 3rd, 2024, from 3:30 – 4:30 p.m. Registration for the April workshop on UDL is already open.

As always, CATL also welcomes you to connect with us if you’d like to learn more about any of these topics. Send us an email or request a consultation to get started!